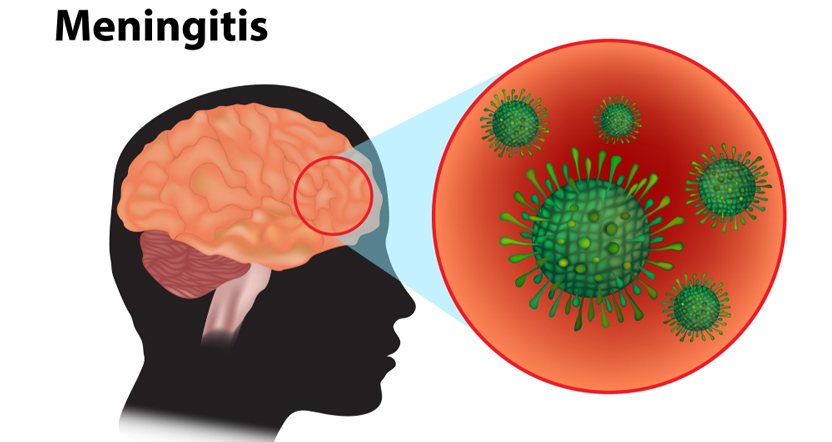

Meningitis is a potentially fatal medical condition typically caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or non-infectious factors such as autoimmune diseases, cancer/paraneoplastic syndromes, or drug responses. Prior to the development of antibiotics, the disease was always fatal. However, despite significant advancements in healthcare, the condition still has an annual mortality rate of about 25%.

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of bacterial meningitis in the United States is approximately 1.38 cases per 100,000 people, with a 14.3% case fatality rate.

The area of sub-Saharan Africa known as “the meningitis belt,” which stretches from Ethiopia to Senegal, has the highest prevalence of meningitis worldwide.

Mode of Transmission and Infection

There are two common ways that meningitis is acquired:

- Hematogenous inoculation

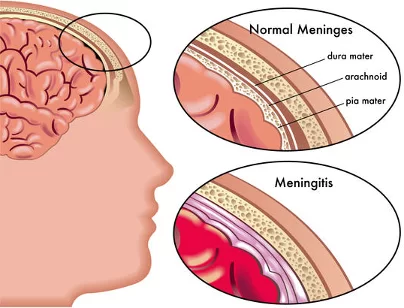

Following the mucosal invasion, bacteria load the nasopharynx and enter the bloodstream. When they reach the subarachnoid region, they penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and induce an immune-mediated inflammatory response.

- Contiguous direct spread

Organisms can enter the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the adjacent tissues (otitis media, sinusitis), foreign bodies (medical equipment, penetrating trauma), or surgical operations.

Viruses can enter the central nervous system (CNS) via hematogenous inoculation or retrograde transmission along neural pathways.

Risk Factors

- Chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, diabetes, adrenal insufficiency, and renal failure

- Old age

- Insufficient vaccination

- Immunosuppressed illnesses (AIDS, congenital immunodeficiencies, transplant patients, and iatrogenic)

- Visiting endemic regions (Northern U.S. for Lyme disease; Southwest U.S. for cocci).

- Vectors (ticks, mosquitoes)

- Conditions related to the consumption of alcohol

- Bacterial endocarditis

- Cancerous conditions

- Utilizing of IV drugs

- Sickle cell anemia

- The splenectomy

Early-stage Meningitis Symptoms

Depending on the host’s age and immune state, meningitis can manifest with various symptoms that develop over several hours or over 1 to 2 days. Photophobia, stiffness or soreness in the neck, and fever are common symptoms. Headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, confusion, delirium, and irritability are more non-specific features. Symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure, such as seizures, impaired mental status, and neurologic impairments, indicate a poor prognosis.

Symptoms in Newborns and Babies (Neonatal/Pediatric Meningitis)

Newborns and infants may exhibit the following symptoms of meningitis:

- Elevated temperatures.

- Sobbing all the time.

- Being extremely tired or agitated.

- Difficulty waking up.

- Being lethargic or inactive.

- Inadequate nourishment.

- Vomiting

- A protrusion in the baby’s head’s soft area.

- Stiffness around the neck and body.

Physical Examination

The analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which includes white blood cell count, glucose, protein, culture, and occasionally polymerase chain reaction (PCR), is used to diagnose meningitis. A lumbar puncture (LP) is used to extract CSF, and the opening pressure can be monitored.

Other tests include:

- Viral meningitis: some PCRs and multiplex

- Fungal meningitis: India ink stain for Cryptococcus, CSF fungal culture, Mycobacterial meningitis: CSF Culture and Acid-fast Bacilli Smear

- CSF burgdorferi antibodies in Lyme disease

The CSF sample should ideally be taken up before starting antimicrobial treatment. However, antibiotics should be started before doing the LP if the patient is very sick and the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is taken seriously.

Read Also: Early Signs of Lupus in Females

Complications

The median risk of complications after discharge was 19.9%, according to a 2010 meta-analysis of a group of pediatric patients. H. influenza was the most frequently isolated organism in this study, followed by S. pneumoniae. Hearing loss accounted for 6% of the most frequent sequelae, with behavioral (2.6%) and cognitive (2.2%) problems, motor deficiencies (2.3%), seizure disorders (1.6%), and visual impairment (0.9%) following closely behind.

Other problems include:

- Cerebral edema, which is brought on by an increase in intracellular fluid in the brain, raises intracranial pressure.

- The condition of hydrocephalus

- Problems with the cerebrovascular system

- Specific neurologic abnormalities

Management and Treatment

- Hospital treatment

All cases of bacterial meningitis should be treated in hospitals because the condition can lead to major complications and needs constant monitoring. Hospital treatment is mandatory also for severe viral meningitis.

Among the treatments are face masks for respiratory issues, IV antibiotics, and fluids to avoid dehydration.

In certain situations, steroid treatment can help reduce swelling surrounding the brain.

Meningitis patients may need to stay in the hospital for a few days, and in other cases, they may require weeks of treatment.

It could take some time for you to feel completely recovered, even after returning home.

- Home-based treatment

If you or your kid gets mild meningitis and examinations indicate that the cause is a viral infection, you will typically be allowed to return home from the hospital. Usually, this kind of meningitis heals on its own without any significant issues. Most people recover in several days. You could be recommended to obtain lots of sleep in the interim and take pain relievers for general pains or headaches. If you have any nausea or vomiting, take anti-sickness drugs. Seek medical care if you feel worse or are unable to control your symptoms at home.

Vaccination: (When Did Meningitis Vaccine Become Mandatory?)

One safe method of developing protection against some of the common causes of meningitis is vaccination. The community as a whole ultimately benefits from immunizing people who are most at risk of acquiring the disease, as it protects them from it and stops it from spreading across communities.

- The MenB vaccination

Meningococcal group B bacteria, which frequently cause meningitis in young children in the UK, are prevented with the MenB vaccine. The recommended vaccination schedule is as follows: 8 weeks for infants, 16 weeks for a second dose, and 1 year for a booster.

- 6-in-1 vaccination

The DTaP/IPV/Hib/Hep B vaccine, sometimes referred to as the 6-in-1 vaccine, protects against polio, hepatitis B, whooping cough, tetanus, diphtheria, and Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib). One type of bacteria that can cause meningitis is called Hib. At 8, 12, and 16 weeks, the vaccine is administered three times.

- Vaccine against pneumococci

Meningitis and other severe diseases brought on by pneumococcal bacteria can be prevented with the pneumococcal vaccine. At 12 weeks, babies are given two separate shots of the pneumococcal vaccine, with a booster dose administered at 1 year of age. Adults 65 and older can only take one dose.

- The Hib/MenC vaccination

The meningococcal group C bacteria, which can cause meningitis, are protected against by the meningitis C vaccine. At 1 year of age, babies receive the combined Hib/MenC vaccine.

- MMR vaccination

Protection against measles, mumps, and rubella is provided by the MMR vaccine. These infections may lead to in meningitis as a side effect. Babies are typically vaccinated at 1 year of age. When they are three years and 4 months old, they will receive a second dose.

- The MenACWY vaccination (teenagers’ vaccine):

The MenACWY vaccine protects against meningococcal groups A, C, W, and Y, the four types of bacteria that can cause meningitis. Teenagers 14 years of age and older are eligible to receive the immunization. Additionally, it is available to those up to 25 who have never received a MenC vaccine.

Teenage Meningitis Vaccine Side Effects

The majority of MenAWCY vaccination adverse effects are minor and transient.

Typical adverse effects include discomfort, swelling, or itching at the site of administration

- Headache and nausea or vomiting

- A rash, irritability, sleepiness, and appetite loss

- Feeling ill overall

Rarely, sometimes more severe side effects occur, such as a strong allergic reaction. Your vaccine provider will have received training on how to handle and promptly treat allergic reactions.

![]()

![]()

Reasons Not to Get the Meningitis Vaccine:

In particular circumstances, including allergies, moderate to severe acute illnesses, potential side effects or complications, or pregnancy, your physician may advise you to postpone or skip the vaccination.

Read Also: What Are the Top 10 Symptoms of High Blood Pressure?

Summary

Public education is necessary to avoid this infection. Patients and parents should be informed about vaccine-preventable meningitis (H. influenza type B, S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, measles, and varicella) by all healthcare professionals, including nurses, doctors, and pharmacists. Overall, the introduction of widespread vaccination has reduced the prevalence of meningitis. When there is a family member with Neisseria and H. influenza type B meningitis, family members should be informed about the necessity of prophylactic treatment. It is important to inform all contacts about the infection’s symptoms and when to visit the hospital emergency room again.

References

- Hersi, K., Gonzalez, F. J., & Kondamudi, N. P. (2023). Meningitis. In StatPearls (Internet). StatPearls Publishing. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459360/.

- Thigpen, M. C., Whitney, C. G., Messonnier, N. E., Zell, E. R., Lynfield, R., Hadler, J. L., Harrison, L. H., Farley, M. M., Reingold, A., Bennett, N. M., Craig, A. S., Schaffner, W., Thomas, A., Lewis, M. M., Scallan, E., Schuchat, A., & Emerging Infections Programs Network. (2011). Bacterial meningitis in the United States, 1998-2007. New England Journal of Medicine, 364 (21), 2016-2025.

- Güldemir, D., Turan, M., Bakkaloğlu, Z., Nar Ötgün, S., & Durmaz, R. (2018). [Optimization of real-time multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of acute bacterial meningitis and Neisseria meningitidis serogrouping]. Mikrobiyoloji Bülteni, 52 (3), 221-232.

- Edmond, K., Clark, A., Korczak, V. S., Sanderson, C., Griffiths, U. K., & Rudan, I. (2010). Global and regional risk of disabling sequelae from bacterial meningitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 10 (5), 317-328.