Heavy menstruation is a risk factor for iron-deficiency anemia due to the amount of iron lost per...

Read MoreIron Deficiency Without Anemia

Introduction

The most prevalent mineral deficiency is iron deficiency, iron deficiency anemia affects 20% of the world’s population. Iron deficiency without anemia is even more common.

Anemia is the most well-known consequence of iron deficiency because hemoglobin, a component of red blood cells, contains about 70% of the iron in adults.

However, it is now clear that iron deficiency without anemia has negative consequences.

Symptoms of Iron Deficiency Without Anemia

Iron is a crucial element that is necessary for many metabolic pathways and responsible for oxygen delivery to the body’s organs and tissues.

Therefore, a deficiency can cause a variety of symptoms that are non-specific and may not be initially identified as being due to iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency without anemia has been associated with:

- Weakness.

- Fatigue.

- Reduced exercise performance.

- Difficulty in concentrating.

- Poor work productivity.

- Neurocognitive dysfunction including irritability.

- Fibromyalgia syndrome.

- Restless legs syndrome.

- Symptom persistence in patients treated for hypothyroidism.

- Poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants born to mothers with iron deficiency.

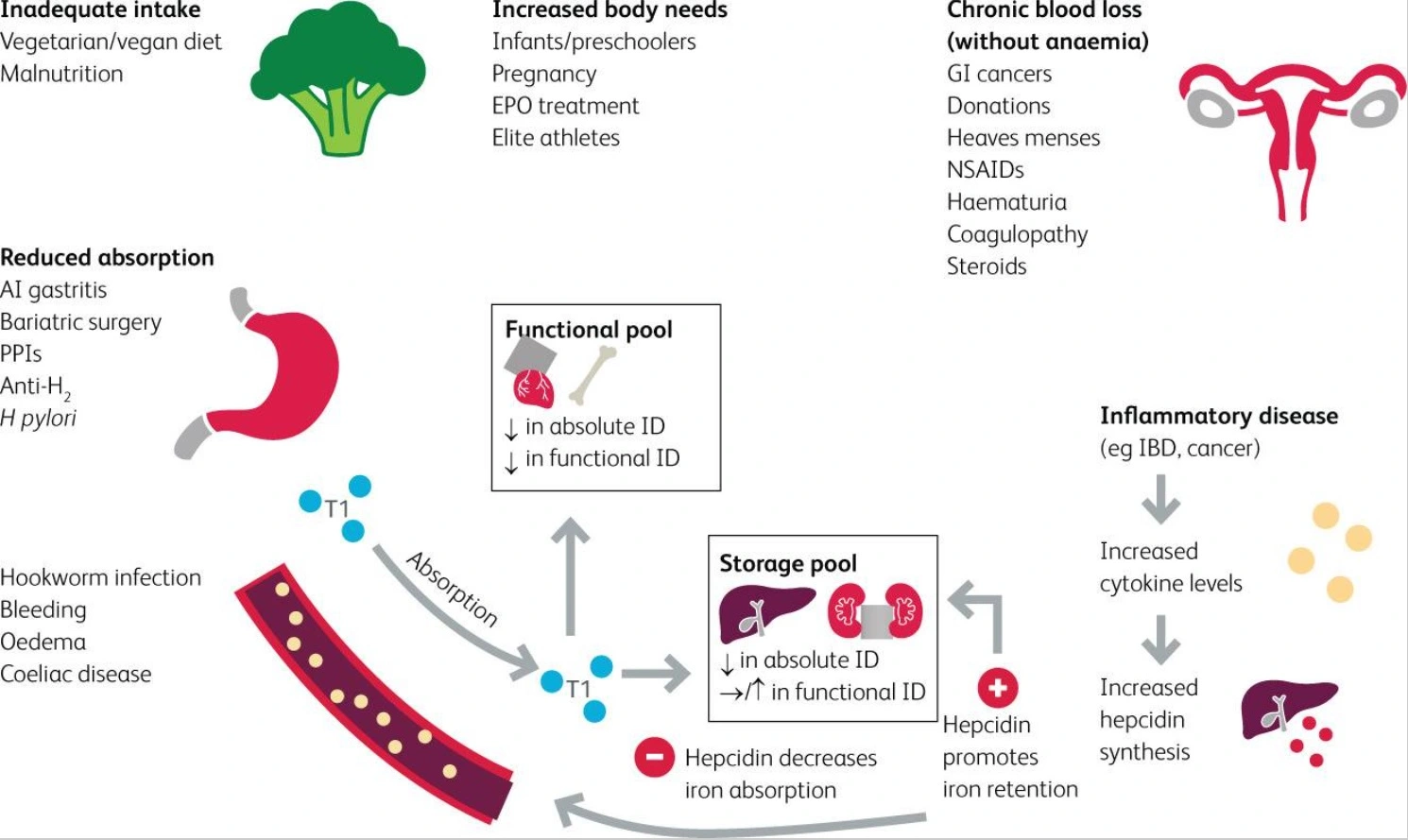

Causes of Iron Deficiency Without Anemia

Iron deficiency can occur secondary to: –

- Inadequate dietary intake.

- Increased requirements (e.g., pregnancy and breastfeeding).

- Impaired absorption (e.g., coeliac disease, bariatric surgery).

- Blood loss (e.g., menstrual, blood donation, gastrointestinal).

Causes of Iron Deficiency

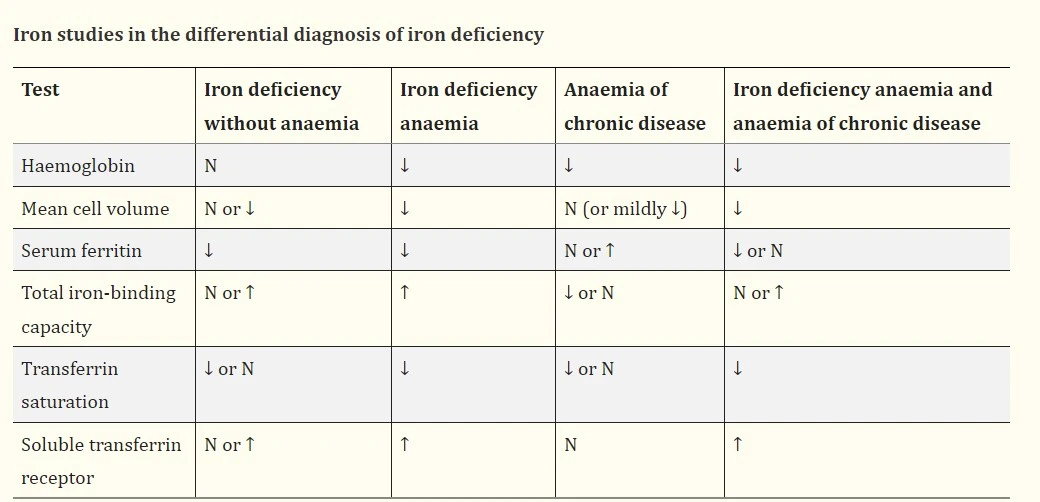

Diagnosing Iron Deficiency Without Anemia

The most precise and sensitive biomarker for determining ID is ferritin, which is a measure of iron stores.

Low ferritin is defined by the WHO as levels below 15 μg/L for adults and <12 μg/L for children.

In clinical practice, ID can be determined when ferritin levels fall below μg/L.

Ferritin is an acute-phase reactant that increases in serum during chronic inflammation.

Iron studies in the differential diagnosis of iron deficiency

A full blood count may indicate changes in iron status before the onset of anemia by falling values for mean corpuscular volume and mean cell hemoglobin as well as increasing red cell distribution width.

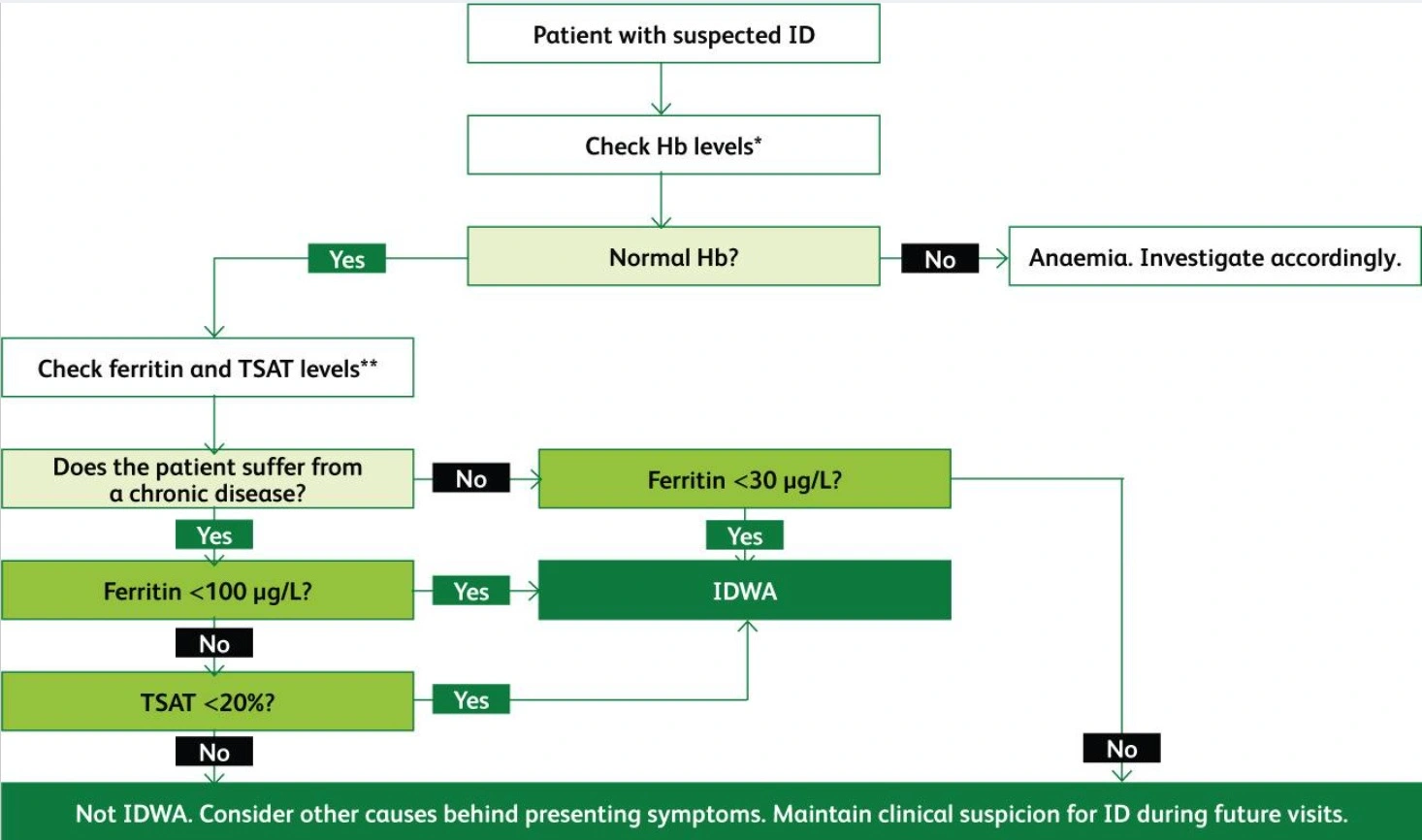

An algorithm for the diagnosis of iron deficiency based on the best current evidence

Treatment of Iron Deficiency Without Anemia

Treatment for non-anemic iron deficiency is similar to that for iron deficiency anemia.

It is necessary to identify the underlying cause and, if possible, correct it.

The integration of dietary heme iron and free iron can optimize nutritional iron intake.

Heme iron (liver, red meat, seafood, and poultry) has a higher gastrointestinal uptake than free iron (plant-based).

Vegetarians can get enough iron by eating a variety of non-heme iron-rich foods like whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, dried fruits, and green leafy vegetables. These methods are unlikely to be adequate for correcting the iron deficiency.

Iron absorption inhibitors (tea, coffee, cocoa, and red wines) should be avoided.

Patients who are asymptomatic and not at risk for poor absorption should use this strategy.

Iron supplements

The first-line and safest treatment for symptomatic patients or those who are at risk of developing anemia is oral iron therapy. It is convenient and cost-effective.

Although there are many different types of iron supplements, ferrous salts (fumarate, sulfate, and gluconate) are preferred because they are most readily absorbed.

According to guidelines, patients should be advised to take their iron supplements either one hour before or two hours after food.

Sometimes compromising on the timing of the dose is possible if it helps the patient adhere to therapy.

While oral supplementation has many benefits, gastrointestinal side effects like nausea, epigastric pain, and diarrhea decrease adherence.

Although iron polymaltose complex and controlled-release preparations are reported to have a lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects, their cost restricts their use.

There are four intravenous preparations available: ferric carboxymaltose, ferric derisomaltose, iron polymaltose, and iron sucrose.

Because of its negative side effects, such as hypophosphatemia and permanent skin staining, the use of intravenous iron should be limited.

If systemic infection is present, intravenous iron should not be administered to prevent the possibility that iron could encourage microbial growth and interfere with immune responses.

The main indications for intravenous iron include:

- Unsuccessful oral therapy – failure, poor adherence, intolerance

- Malabsorption (e.g., coeliac disease, bariatric surgery)

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Chronic kidney disease receiving erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs

- A Rapid increase in iron required (e.g., pre-operatively for urgent surgery or following acute blood loss).

Summary

The most prevalent mineral deficiency is iron deficiency, iron deficiency anemia affects 20% of the world’s population. Iron deficiency without anemia is even more common.

Anemia is the most well-known consequence of iron deficiency because hemoglobin, a component of red blood cells, contains about 70% of the iron in adults.

Iron deficiency without anemia has been associated with:

- Weakness.

- Fatigue.

- Reduced exercise performance.

- Difficulty in concentrating.

- Poor work productivity.

- Neurocognitive dysfunction including irritability.

- Fibromyalgia syndrome.

- Restless legs syndrome.

- Symptom persistence in patients treated for hypothyroidism.

- Poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants born to mothers with iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency can occur secondary to: –

- Inadequate dietary intake.

- Increased requirements (e.g., pregnancy and breastfeeding).

- Impaired absorption (e.g., coeliac disease, bariatric surgery).

- Blood loss (e.g., menstrual, blood donation, gastrointestinal).

The most precise and sensitive biomarker for determining ID is ferritin, which is a measure of iron stores.

Low ferritin is defined by the WHO as levels below 15 μg/L for adults and <12 μg/L for children.

In clinical practice, ID can be determined when ferritin levels fall below 30 μg/L.

A full blood count may indicate changes in iron status before the onset of anemia by falling values for mean corpuscular volume and mean cell hemoglobin as well as increasing red cell distribution width.

The first-line and safest treatment for symptomatic patients or those who are at risk of developing anemia is oral iron therapy. It is convenient and cost-effective.

Although there are many different types of iron supplements, ferrous salts (fumarate, sulfate, and gluconate) are preferred because they are most readily absorbed.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

I'm sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let me improve this post!

Tell me how I can improve this post?

References

- Balendran, S., & Forsyth, C. (2021, December). Non-anaemic iron deficiency. Australian prescriber. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from PubMed

- Al-Naseem, A., Sallam, A., Choudhury, S., & Thachil, J. (2021, March). Iron deficiency without anaemia: A diagnosis that matters. Clinical medicine (London, England). Retrieved December 9, 2022, from PubMed

Anemia was found to be common in COVID-19 patients who were hospitalized, also, it was linked to...

Read MoreDiamond Blackfan anemia (DBA) is a form of congenital anemia that is characterized by pure red cell...

Read MoreIron deficiency anemia (IDA) is the most common cause of anemia and the most treatable of all...

Read MoreRecent Posts

-

SAPHO Syndrome | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatments

-

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

Gastric Ulcers | Causes, Symptoms, Complications & Treatments

-

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

The 4 Stages of HIV Infection | Ultimate Guide

-

Good’s Syndrome | Symptoms, Causes & Treatments

-

Acquired Angioedema | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

Rheumatoid Arthritis | Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis & Treatments

-

Acute Pancreatitis | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Pernicious Anemia | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Sickle Cell Anemia | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Aplastic Anemia | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Diamond Blackfan Anemia | Causes, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Sideroblastic Anemia | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

Organic Dust Toxic Syndrome (ODTS) | Symptoms, and Treatments