Radiation exposures from radiological procedures represent the largest part of … Radiation dose limits for of any...

Read MoreSilicosis | Causes, Diagnosis, and Prevention

Introduction

Silicosis is a type of pneumoconiosis caused by the inhalation and deposition of dust containing crystalline silicon dioxide, typically in its most common form, which is called α -quartz.

It is the most prevalent occupational lung disease worldwide, particularly in developing nations.

Severe cases may even be fatal or disabling.

The following occupations are at risk: brickwork, pottery making, handling crushed silica flour (which is used in many manufacturing processes), mining, quarrying, tunneling, sandblasting, and foundry work.

Chronic silicosis occurs after several years of exposure, takes several years to develop, and is associated with restrictive lung function that worsens over time and may progress even if silica exposure is discontinued.

Causes of Silicosis

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is the most abundant mineral on the planet and is found in both crystalline and amorphous forms.

Amorphous-form inhalation does not seem to result in clinically significant complications, whereas crystalline-form inhalation can result in pulmonary disease.

In workplaces, quartz, tridymite, and cristobalite are the most prevalent free crystalline forms of silica.

Quartz can be found in varying concentrations naturally in rocks such as sandstone (67% silica) and granite (25-40% silica).

The minerals cristobalite and tridymite are created naturally in lava, they are formed when quartz or amorphous silica is heated to extremely high temperatures

They can also be formed in the manufacture of silica bricks (refractory bricks) used in industrial furnaces.

Less common types include keatite, coesite, and stishovite.

Silicosis - Causal Exposures/Industries

Mining: Silica is frequently found in the surrounding strata in coal and other mineral mines.

Tunnel drillers/blasters, roof bolters, and transportation crew are at the highest risk (although face workers and others are also exposed)

Quarries: workers responsible for blasting, cutting, and transporting stone.

Stone-working:

- Stone-masonry (granite dressing and grinding).

- Flint-knapping.

Heavy engineering and manufacture:

- Shot blasting.

- Preparation and use of grinding wheels/stones (historically, cutlers).

- Use of compressed airlines to clean off silica-containing material.

Foundries:

- Sand-moulding

- Shot-blasting

- Compressed air cleaning of molded items

- Fettling

Ceramics and pottery making

Brick-making.

Conditions that have been Associated with Silica Exposure

Silicosis

- Chronic silicosis.

- Accelerated silicosis.

- Silicoproteinosis.

Infections

- Tuberculosis (pulmonary and extrapulmonary).

- Other mycobacterial, fungal, and bacterial lung infections (usually with silicosis).

Airway disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Malignant disease

- Lung cancer.

- Gastric, oesophageal, and several others (possible association).

Autoimmune diseases

- Scleroderma.

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

Renal diseases

- Chronic renal disease.

Clinical Features

Silicosis is classified into three types:

Acute: early onset of dry cough and dyspnea within a few months of heavy exposure to fine dust (e.g., sand-blasting).

CXR confirms patchy small airway consolidation (appearance similar to pulmonary edema).

progression over 1-2 years, with respiratory failure.

Subacute: gradual onset of dry cough and dyspnea after moderate exposure over years.

CXR confirms upper- and mid-zone nodular fibrosis along with a classical feature of ‘egg-shell’ calcification of the hilar lymph nodes.

PMF can occur, with the coalescence of the fibrotic nodules.

The restrictive pattern of impaired lung function.

Chronic: nodules on CXR develop slowly over many years after low-level exposure.

Diagnosis of Silicosis

Diagnosis is based on a history of silica exposure and the classic X-ray findings that include: –

- Widespread rounded dot-like nodular opacities in both lung fields, particularly in the mid and upper zones.

- Visible deposits of calcium are called calcification in the lymph nodes.

- The lung tissue under a microscope reveals that each focus of fibrosis begins as a concentric, fingerprint-like lesion made of collagen fibers with silica crystals trapped inside.

- These silicotic nodules combine to form larger masses of scar tissue, which, as the disease worsens, results in an increasingly restrictive defect and shortness of breath.

Management of Silicosis

Since there is no definitive treatment, management is supportive.

The disease cannot be treated, reversed, or stopped.

The worker should be kept from further exposure to silica to prevent a more rapid and severe progression, but the condition will still worsen.

Sputum is routinely examined for tubercle bacilli, and if an infection is found, it is treated with the standard anti-tuberculous chemotherapy.

10–30% of silicosis cases progress after removal from exposure.

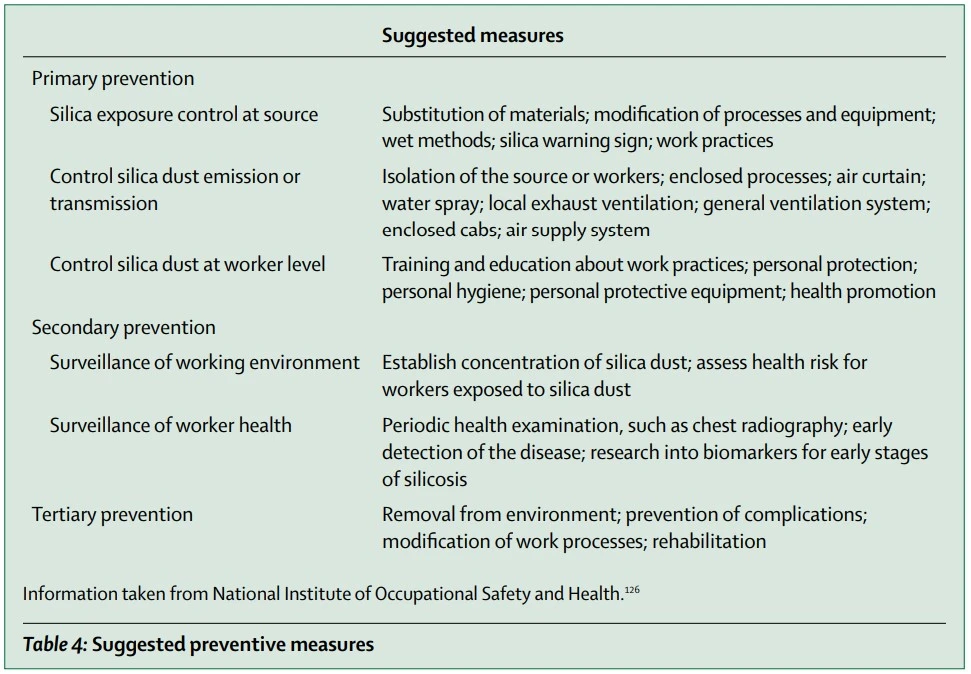

Preventive Measures for Silicosis

Silicosis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in both developed and developing countries.

Therefore, additional efforts are needed to recognize and manage silica hazards globally.

In 1995, the Global Program for the Elimination of Silicosis was established by a joint International Labour Organization and WHO committee.

Before beginning a job, it is important to evaluate the potential of silica exposure, especially in industries that have previous reports of silicosis.

All industries with silica exposure should conduct periodic monitoring of respirable silica.

Cyclone or impact dust sampler can be used to collect respirable dust.

The Talvitie (phosphoric acid) method, infrared spectrophotometry, or x-ray diffraction can be used to determine the free silica content of respirable dust.

The primary method of silicosis prevention is the avoidance or control of silica exposure through various measures directed at the source, transmission, and workers.

Source control can include banning sandblasting and substituting metal grits for abrasive blasting, as is done in most developed countries, including Europe.

When source control is not practical or sufficient, additional measures should be taken to isolate or capture dust and introduce clean air to protect workers from hazardous silica exposure.

Administrative measures, such as short working hours or job rotation, can be used in workplaces with high levels of dust.

For short-duration tasks, personal protection equipment like respirators is helpful.

However, it may not be completely effective in high-dust workplaces and should only be used as a last resort for routine full-shift protection.

Suggested Preventive Measures

Summary

Silicosis is a type of pneumoconiosis caused by the inhalation and deposition of dust containing crystalline silicon dioxide, typically in its most common form, which is called α -quartz.

The following occupations are at risk: brickwork, pottery making, handling crushed silica flour (which is used in many manufacturing processes), mining, quarrying, tunneling, sandblasting, and foundry work.

Amorphous-form inhalation does not seem to result in clinically significant complications, whereas crystalline-form inhalation can result in pulmonary disease.

Silicosis is classified into three types: acute, subacute, and chronic.

Diagnosis is based on a history of silica exposure and the classic X-ray findings

Since there is no definitive treatment, management is supportive.

The worker should be kept from further exposure to silica to prevent a more rapid and severe progression, but the condition will still worsen.

All industries with silica exposure should conduct periodic monitoring of respirable silica.

The primary method of silicosis prevention is the avoidance or control of silica exposure through various measures directed at the source, transmission, and workers.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 5 / 5. Vote count: 1

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

I'm sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let me improve this post!

Tell me how I can improve this post?

References

- Guidotti, T. L. (2011). Global Occupational Health. Oxford University Press.

- Sadhra, S. S., Bray, A., & Boorman, S. (2022). Oxford Handbook of Occupational Health. Oxford University Press.

- W;, L. C. C. Y. I. T. C. Silicosis. Lancet (London, England). Retrieved December 12, 2022, from PubMed

- Mlika, M., Adigun, R., & Gossman, W. G. (2020). Silicosis (Coal Worker Pneumoconiosis). PubMed; StatPearls Publishing From PubMed

Occupational diseases are conditions that are linked to a specific job or industry. This article will provide...

Read MoreNoise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is a type of progressive deafness caused by noise exposure due to permanent damage to the...

Read MoreSilicosis is a type of pneumoconiosis caused by the inhalation and deposition of dust containing crystalline silicon...

Read MoreRecent Posts

-

SAPHO Syndrome | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatments

-

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

Gastric Ulcers | Causes, Symptoms, Complications & Treatments

-

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

The 4 Stages of HIV Infection | Ultimate Guide

-

Good’s Syndrome | Symptoms, Causes & Treatments

-

Acquired Angioedema | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

Rheumatoid Arthritis | Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis & Treatments

-

Acute Pancreatitis | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Pernicious Anemia | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Sickle Cell Anemia | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Aplastic Anemia | Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Diamond Blackfan Anemia | Causes, Diagnosis and Treatments

-

Sideroblastic Anemia | Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

-

Organic Dust Toxic Syndrome (ODTS) | Symptoms, and Treatments